Strengthening Africa's Capacity In Manufacturing Vaccines And Medicines

This is the 1st post in a blog series to be published in 2023 by the Secretariat on behalf of the AU High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies (APET) and the Calestous Juma Executive Dialogues (CJED)

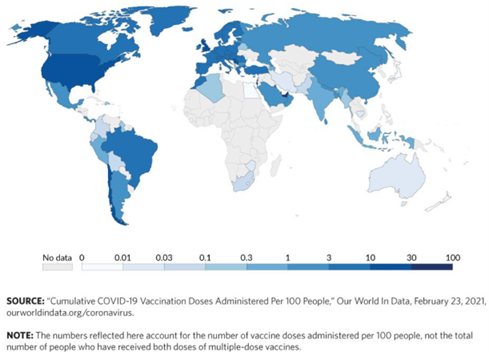

The prevalence of infectious diseases are particularly elevated in Africa because of environmental factors and limited health infrastructure such as health facilities and services. Diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria, and other illnesses have spread rapidly. According to reports, thousands of children under the age of five die each year as a result of diseases such as malaria. For example, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa between 2014 and 2016 resulted in over 11,000 fatalities.[1] Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in over 12.38 million cases of infection and approximately 257 thousand deaths between February 2020 and October 2022 across the African continent.[2] Thus, the continent that did not initiate COVID-19 and effectively used limited resources to keep deaths and infections below global averages may suffer severely from the pandemic's socio-economic repercussions due to difficulties surrounding vaccine access (see figure 1).[3]

Figure 1: Africa’s Lack of Access to COVID-19 Vaccines

Remarkedly, African countries are significantly relying on the importation of diagnostics, medications, vaccines, personal protective equipment, and other medical supplies to manage these diseases. For example, Africa is importing almost 99% of vaccinations for diseases, and over 95% of medications, despite consuming approximately 25% of the world's vaccine production[4]. This is demonstrating the need to have its manufacturing capacity and infrastructure for vaccines and medicines to address access to medication and enhance cost-effectiveness for the continent’s citizenry.

Africa's reliance on other countries for medicines and vaccines and its poor vaccine manufacturing capabilities contribute significantly to the continent's inadequacy in addressing these prevalent diseases and pandemics. However, simply expanding the importation of COVID-19 vaccinations to African countries cannot be considered a long-term solution. Rather African countries should develop their capability to manufacture and distribute medicines and vaccines.

For Africa to enhance its capacity to address emerging pandemics and diseases, countries have recognised their need to expand their capacity to manufacture vaccines and medicines. To this end, in April 2021, the African Union (AU) through the African Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) developed the Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM) Framework for Action. This framework is instituting mechanisms to improve Africa’s current vaccine manufacturing environment and implement programmes to unlock Africa’s potential to scale up the development and manufacturing of vaccines over the next two decades.[6]

The African Union Commission and Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) have called on governments, multilateral organizations, philanthropies, the private sector, and civil society organizations to support the full implementation of Africa’s New Public Health Order to drive global health security. The Public Health Order is aimed at protecting Africa’s health and economic security as it seeks to accomplish the goals of the AU’s Agenda 2063 to accomplish universal health by 2030. Therefore, enhancing local production of vaccinations, diagnostics, and treatments can enhance the continent’s health systems, and enhance the capability to respond to pandemics and other health crises. In this way, Africa will be able to manufacture at least 60% of vaccines domestically by 2040, enhancing its self-reliance while it meets its vaccination needs.[7]

In 2007, the AU adopted the Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan for Africa (PMPA) to hasten and expand local pharmaceutical production.[8] As a result, Ethiopia, South Africa, Senegal, Nigeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria have since started vaccine production and manufacturing. However, because of the continent's unpredictable supply chains and the limited local scientific skills capacity, the vaccines and medicines production remain low. Consequently, locally produced vaccines and medicines are largely augmented by imports. Other limiting factors include inadequate investments by African governments in vaccine manufacturing, and ineffective regulatory capacity for vaccine research, development, and production. There is also limited support that is frustrating efforts of vaccine production in Africa by global vaccine stakeholders that have resulted in uncertainties towards meeting the demands of Africa-made vaccines.[9]

The African Union High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies (APET) recommends African countries to enhance their capabilities to manufacture vaccines and medicines. This can be accomplished by adopting several mitigation strategies to enhance vaccine and medicine production in Africa. For example, APET is inspiring African countries to strengthen their training capacity education policies to encourage pharmaceutical research and development. Such efforts can encourage skills capacity strengthening and entrepreneurship. Furthermore, the panel encourages African countries to improve and harmonise their regulatory systems to enhance the quality assurance of local manufacturers in order to match international standards when manufacturing medical consumables, materials, medicines, and vaccines.

African countries should also collaboratively coordinate their national and regional policies and initiatives to promote local production. Such efforts can assist economies of all sizes to create synergies, share the workload and avoid wasteful duplication. As such, the African market integration and trade facilitation can exploit regional economic integration platforms such as the Economic Community of West African States, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, and the African Continental Free Trade Agreement. Consequently, more integration can result in sustainable manufacturing of products in high demand in the region and expand access to new markets.

APET emphasizes that it is important for African countries to augment their political, policy, and regulatory support for vaccine manufacturing in Africa. Fundamentally, African leaders need to increase their investment commitments and policy implementation to enhance local vaccine manufacturing efforts. This can significantly improve the regionalisation and integration of vaccine markets across the continent. Access to finance and investments in local vaccine manufacturing can enhance vaccine production infrastructure and skills through collaborative partnerships and joint ventures.

APET notes that African countries can also draw lessons and replicate past successes in producing and distributing vaccines and medicines in Africa. For example, in 2010, African leaders expanded efforts to eradicate Group A Meningitis epidemic in Africa through the Meningitis Vaccine Project (MVP). This global collaboration involved public health experts, World Health Organization, Non-Governmental Organisations, and commercial firms to produce the “MenAfriVac”. The “MenAfriVac” was a cost-effective vaccination that was utilised to conduct large immunisation campaigns that significantly reduced meningitis. This also facilitated technology transfer, regulatory approval, and testing to enhance the local production of vaccines and medicines.[10]

Since Africa only manufactures approximately 0.1% of the global supply of vaccines, APET opines that there is a market failure that requires urgent attention. This can be accomplished by creating superior vaccine supply resilience for Africa through domestic production.[11] Hence the continent should create this potential multi-million industry almost from scratch through the support of African governments and manufacturers. For example, the continent has managed to produce more than 11 billion doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. However, due to vaccine hoarding and export restrictions coupled with the lack of regional vaccine supply across the continent, Africans continued to lose their lives due to the delays in access to doses. Regrettably, if this is left unchecked, it can lead to more catastrophic health insecurities.[12] If the vaccine production limitation in Africa were to be meaningfully expanded, Africa could enhance her pandemic preparedness, create a greater vaccine supply resilience for African nations for a comprehensive range of vaccine-preventable diseases, and practically create a sustainable multi-billion-dollar industry.

APET observes the various vaccine manufacturing initiatives that are currently underway as approximately 30 vaccine manufacturing activities were started across the continent. These initiatives were based on the African Union’s aspirations to develop, produce, and supply more than 60% of the vaccine doses required on the continent by 2040.[13] However, without careful planning and coordination, the threat could be that even with significant capital investment, these initiatives will not survive in the long term. Such shortcomings could have substantive negative impacts on existing vaccine markets.

Hence, APET advises African countries to formulate and implement a comprehensive approach to finance the fixed overhead costs, enhance capacity strengthening of relevant skilled labour, intensify quality assurance and control, and strengthen the reliability of vaccine production. Consequently, this can make the vaccine costs competitive and sustainable. For example, the 11 vaccines that the WHO has recommended for every country can cost an equivalent of approximately US$1,300 in the United States of America. However, the same vaccines can cost as low as US$28 for Gavi-eligible countries, which includes several African countries.[14] Notably, when Gavi was first founded, it had five suppliers, which were predominately based in Europe and North America. However, this has since increased to 18 manufacturers with only seven that are in European and North America.

COVID-19 has highlighted the need for a new approach as this Gavi model has exhibited some supply reach limitations. The new approach should involve the expansion of vaccine manufacturing across Africa to boost the regional and global supply of routine vaccines.[15] This process can create a sustainable supply resilience for future pandemic vaccines as Africa is the world’s largest purchaser of vaccines. African countries can support regional manufacturing in Africa. Part of this approach can involve industrial engagements and participation, provide analysis of existing markets, coordinate the vaccine markets to avoid over-crowding markets, and enhance proper regulatory benchmarking.[16]

Expanding the vaccine manufacturing efforts in Africa represents an enormous opportunity to enhance health security across Africa. This can potentially protect African citizens from a wide range of infectious diseases and further establish African vaccine manufacturers as important global suppliers. APET realises that expanding vaccine production in Africa is a challenging endeavour that requires the coexistence of various components. Most importantly, the developing sector requires extensive coordination amongst a wide range of stakeholders, including pan-African leadership groups, regional economic governments, national governments, private-sector players, and global health actors. This can significantly bolster the sustainability and effectiveness of vaccine and medicine manufacturing in Africa.

Featured Bloggers – APET Secretariat

Justina Dugbazah

Barbara Glover

Bhekani Mbuli

Chifundo Kungade

Nhlawulo Shikwambane

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9358391/.

[2] https://mo.ibrahim.foundation/covid-19-africa-tracker.

[3] https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/02/24/vaccine-geopolitics-could-derail-africa-s-post-pandemic-recovery-pub-83928

[4] ibid

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9358391/.

[6] https://africacdc.org/download/partnerships-for-african-vaccine-manufacturing-pavm-framework-for-action/.

[7] https://africacdc.org/news-item/african-union-and-africa-cdc-launches-partnerships-for-african-vaccine-manufacturing-pavm-framework-to-achieve-it-and-signs-2-mous/.

[8] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2022/02/14/the-future-of-vaccine-manufacturing-in-africa/.

[9] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2022/02/14/the-future-of-vaccine-manufacturing-in-africa/.

[10] https://www.one.org/africa/issues/covid-19-tracker/explore-african-manufacturing/.

[11] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/10/ramping-up-africa-s-vaccine-manufacturing-capability-is-good-for-everyone-heres-why/.

[12] https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/01/12/blog011322-support-for-africas-vaccine-production-is-good-for-the-world.

[13] https://www.gavi.org/news-resources/knowledge-products/expanding-sustainable-vaccine-manufacturing-africa-priorities-support.

[14] Fesenfeld, Michaela & Hutubessy, Raymond & Jit, Mark. (2013). Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Vaccine. 31. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.060.

[15] https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/ramping-africas-vaccine-manufacturing-capability-good-everyone-heres-why.

[16] https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/enhancing-public-trust-in-covid-19-vaccination-the-role-of-governments-eae0ec5a/.