Expanding Agricultural Extension Services For Capacity Strengthening Of Africa's Small-Scale And Subsistence Farmers Using Technology

This is the 12th post in a blog series to be published in 2022 by the Secretariat on behalf of the AU High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies (APET) and the Calestous Juma Executive Dialogues (CJED)

Hunger and malnutrition remain major obstacles to socio-economic development and growth for many African countries. Even though Africa has about 60% of the world's available arable land suitable for agriculture, food production has remained limited, barely feeding the African population adequately.[1],[2] The African Union's Agenda 2063 and the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are socio-economic developmental frameworks aspiring to address the hunger and malnutrition challenges through sustainable agriculture. This can ensure that all African people, particularly children, have adequate and nutritious food throughout the year and even export some of the food.

African countries have noted that sustainable agriculture can be accomplished by strengthening small-scale farmers to produce crops and vegetables for the African continent maximally. This can be realised by providing and enabling equal access to arable land, technology, capacity strengthening through extension services, and access to the markets.[3] Thus, African countries are progressively eradicating food insecurity as supported by the African Union Summit Decision on Accelerated Agricultural Growth and Transformation Framework.

Food insecurity in most African countries is caused by limited-to-weak agricultural systems and delivery services, the unpredictability of optimal farming schedules due to climate change, limited capacity for irrigation systems and overreliance on rains, growing wars, and conflicts.[4] Currently, African countries are only producing 10% of the world's food output and this causes most African countries to rely on food importation so as to boost their food security. [5] Fundamentally, agricultural activities in Africa have been collapsing since the attainment of independence of most countries, as characterised by the limited growth in agricultural production per capita observed from the early 1960s to the 1970s (Figure 1).[6] This declining agricultural trend contrasts with the food production growth observed in other developing regions and impedes the aspirations of most African countries' efforts toward ensuring food security.

![Figure 1: Figure 1. World agricultural production per capita 1961–2005 (index 1961 = 100) (Hazell & Wood, 2008)[7]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Picture1_0.jpg)

Since 30% of the African population remains food insecure, several African governments have been encouraging enhanced subsistence and small-scale farming activities within their countries.[8] Currently, poor households are accessing their food from the market, food generated from subsistence farming, and allocations from public programmes or other households. This contrasts with the expected trends of generating their own food. Despite this, most households and communities increasingly rely on market purchases, up to approximately 90% of their food supplies.[9] Unfortunately, food expenditures account for between 60–80% of their total household income, particularly for low-income households across various African regions.[10] Thus, strengthening the capacity of subsistence and smallholder agriculture can significantly benefit and enhance food security, improve livelihoods, and mitigate the high food price inflations. In addition, the increased productivity of subsistence and smallholder agriculture can ensure long-term food security for the African countries.

Even though most subsistence and small-scale farmers are well trained and knowledgeable after generations of subsistence and small-scale farming, there is still a need for more capacity strengthening to improve their farming capabilities, skills, and sustainability. Farmers can develop crop rotation, rotational grazing, and soil health monitoring methods. These methods can be incorporated into subsistence and small-scale farming to enhance their farming yield in the long term. Nevertheless, to fully accomplish these capacities, farmers should be able to monitor and manage their crops and animals more effectively. This way, they can transform their subsistence and small-scale farming into sustainable job creation and lucrative enterprises.

To monitor these methods, the African Union High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies (APET) advises that African farmers should employ technologies to transform desecrated natural resources, improve their harvests, and address deforestation and human-wildlife conflicts. Thus, access to technologies can enable capacity strengthening to develop climate-smart farming and improve access to drought-resistant crop varieties. This can also enable small-scale and subsistence farmers to manage their farming activities and improve crop yields with well-managed land and water resources. These technologies can also link farmers to markets for their goods to ensure profitability and protection of the natural environment.

Agricultural extension services are usually employed to strengthen Africa's farmers' capacity. These agricultural extension programmes are being implemented across the African continent. Throughout the 20th century, agricultural extension services were primarily implemented by government researchers. This was normally undertaken whenever newly published research was supposed to be disseminated to the masses. In some cases, extension services workers were hired specifically to disseminate agro-information on best practices, research, and technology transfer through a public sector-driven model.[11] However, public sector spending on agriculture has varied widely across the different African regions. In most African regions, limited spending on agriculture impeded the availability of agricultural extension services programmes.

Tanzania has been tackling food insecurity by employing the country's agricultural extension systems. These extension services enable the Tanzanian government to revamp and reform their small-scale farming activities. The country has a population of 55.9 million people, and 25% of the country's gross domestic product is generated from agriculture.[12] Regrettably, 15% of rural households have food insecurities, and the risk of food insecurity threatens an additional 15%. Tanzanian regions such as Dodoma, Tabora, Singida, Mwanza, Kagera, and Manyara observe prevalent food insecurities in 55% of the households and 27% vulnerable to food insecurity.[13] Therefore, improving farming activities within these regions of Tanzania has become a priority for the government. In particular, extension service programmes have been key in bolstering farming productivity and food security.[14]

Historically, agricultural extension programmes enable Tanzanian farmers to access agricultural information to improve their farming capacities. However, these extension services are primarily conducted through face-to-face communication to disseminate information on various farming methodologies and technologies. Through informal education such as rural adult learning, extension programmes assist farmers in developing technical and managerial skills in agricultural-dependent economies such as Tanzania.

Yet, despite the importance of agriculture extension services in Tanzania, the current system of extension services offers limited assistance to farmers because of limited access to these services. This is because a limited number of farmers have direct contact with agricultural field workers due to their dispersed nature and the limited number of extension service providers. For example, one extension field worker is responsible for approximately two villages, which may sometimes translate into approximately 1000 subsistence and small-scale farmers. Consequently, accessibility and the capacity to reach all these farmers become difficult and nearly impossible.

A case in point is a Tanzanian region known as Morogoro which is remote but one of Tanzania's most fertile arable lands.[15] The farming activities in the region result in commercial crops such as sunflower, coconut, sugarcane, sisal, rice, maise, sorghum, cassava, and millet. However, since this region is remote, the farmers are limitedly experiencing timely and effective agricultural extension services. Consequently, this is limiting access to crucial agricultural information that will help farmers of this region improve their farming yields.

In addition, most extension services workers complain about their poor working conditions, such as limited travelling funds and transportation. In some cases, the extension services providers utilise bicycles as modes of transportation to reach hard-to-reach and remote farmers. Such challenging conditions for workers in the extension services programmes lead to the staff profile being male-dominated, without needed gender balance. Unfortunately, this also results in prioritising male farmers over female farmers during engagements as gender representation in capacity building is equally important. Consequently, this ends up impeding female farmers from accessing the extension services offered by their governments, in addition to competing and bureaucratic demands.[16]

APET believes that timely access to essential agricultural information necessitates an effective link between agricultural information sources and farmers. Thus, the employment of various communication technologies is encouraged. Radios and television are the preferred communication technologies as they are readily available and less expensive. This can help African countries better disseminate agricultural extension information to farmers, even in remote areas.

To address its challenges to agricultural extension services access, the Tanzanian government disseminates agriculture extension services through radio and television. By utilising radio and television, Morogoro farmers are accessing agricultural information without the physical presence of the extension workers. Thus, farmers can access information about rain patterns, markets, and pests control information in a timely manner.[17]

The advent of smartphones in Tanzania has also enabled more accessible agricultural extension services for Tanzanian farmers. For example, farmers in the Kilosa District of Tanzania leverage smartphone applications to access timely agricultural extension services and information.[18] Since 2015, in Kilosa District, farmers have been utilising a smartphone application known as Ushaurikilimo. Ushaurikilimo provides agricultural advisory and extension services. The system integrates the farmers' advisory information system and a web-based farmers' advisory system (W-FAIS) through a website or smartphone application.[19] This allows farmers access to information on the best practices on agronomic and post-harvest methodologies for crops, livestock and husbandry operations, veterinary services, and access to community and national markets.

APET notes that the successful government-led extension programmes have had to adapt and, in some way, alter their approach so as to embrace new technologies. For example, the Moroccan government introduced the Green Morocco Plan (Plan Maroc Vert) in 2008 as a multifaceted policy package to encourage significant changes across the country's agricultural sector.[20] As a result, this policy package changed the country's extension services from focusing mainly on production techniques, plant health management, and quality control into a more comprehensive approach. The comprehensive reforms propagated by the Green Morocco Plan integrated other aspects such as professional organisation of farmers, economic and project management, information on state aid and incentives, labelling, branding, marketing, packaging, and food processing.

Furthermore, in partnership with developmental partners, the Moroccan government has facilitated the adaptation of digital technologies to disseminate extension information on agriculture to Moroccan farmers. For example, in 2012, IBM collaborated with the Ministry of Agriculture to exploit a cloud-based system that experts and institutions could utilise to disseminate knowledge and enable experience sharing with local farmers.[21] This platform could also be utilised for training purposes and managing outreach programmes and efforts. This platform also allows various Moroccan government agencies to share information about farming activities.

Then again, this approach is particularly suitable for Morocco because of its well-managed internet services and access to smartphones. This access also enables small-scale farmers to deal directly with wholesalers and large-scale intermediaries to make the agricultural value chain more efficient. APET notes that this may not be the same for other African countries with limited internet infrastructure. Thus, using traditional technologies such as radio and television becomes useful in such instances.

The Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture and its Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA) have also established several initiatives to enhance their farmers' productivity and capacity.[22] This is specially targeted toward the country's priority crops promoting traditional extension service methods such as in-person and smart technology-based training. For example, in 2014, the ATA introduced a hotline that enabled farmers to seek agricultural advice and crop-specific tutorials.[23] This free and voice-based hotline is improving agricultural literacy rates across the country. Furthermore, reports have demonstrated that this service has been well accepted, with approximately one million registered callers during the first year of operation.

Historically, the technology and skills transfer programmes steered by Africa's private sector have primarily focused on export-oriented industries such as sugar, coffee, and tea. Yet, within the non-exported crops, the skills-transfer programmes have been lacklustre and, in some cases, absent.[24] Nonetheless, this is beginning to change as some countries such as Kenya are deliberately and comprehensively strengthening their extension services. Fundamentally, Kenya's private sector is simultaneously strengthening the capacity of its food manufacturing and technology activities. For instance, Kenya's manufacturing enables its farmers to acquire and establish sustainable market linkages.[25] Thus, the country's technology expansion within the country is enabling innovative extension services.

Kenya's dairy giant, Brookside, is amplifying its agricultural extension services. The company has a 44% market share in Kenya's dairy market and currently expanding its export markets throughout East Africa and progressively within the Middle East.[26] To meet these demands, the company relies on approximately 160 thousand small-scale farmers for its milk supply.[27] These small-scale milk suppliers continue to grow due to the company's aggressive outreach programmes with a guaranteed and consistent market for the small-scale milk producers. Then again, since the milk product has a short shelf life, the company's extension services are strengthening the capacity of local milk producers' high-quality and technology-based milk production.

Through this campaign, the Brookside company has largely succeeded in addressing inherent challenges with small-scale milk production. These include the seasonality of production, substandard provision of inputs and veterinary services, supply chain disintegration, as well as limited animal husbandry skills and knowledge. To this end, the Brookside company has developed extension services programmes to strengthen the capacity of farmers by training them through regular "field days" to acquire best husbandry practices. These training programmes are also helping farmers learn about the new developments within the dairy industry. Additionally, the Brookside company provides artificial insemination services and facilitates farmers' access to high-quality drugs and feed for their cows. The company has created a team of trained agricultural personnel to build and strengthen the capacity of Kenya's farmers. Interestingly, these extension services are offered to dairy farmers on credit and subsequently taken from their milk revenues to ascertain the sustainability of the extension services.

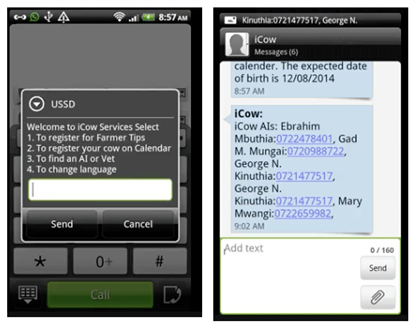

Furthermore, Kenya's high literacy rates, smartphone access, and the ongoing technology surge have enabled the expansion of domestic smartphone mobile applications. Smartphone applications focusing on agricultural applications have expanded the country's agricultural outputs. For example, an application known as "iCow" targets dairy farmers and utilises the internet through short-message services (SMS) and voice-based applications to afford many valuable extension services to farmers. These extension services include tips about breeding and ideas and recommendations on animal nutrition.

The iCow application is also linking farmers to veterinary and artificial insemination services. Most importantly, the iCow application essentially allows farmers to generate a detailed and customised profile for each of their cows.[28] This presents features such as custom-tailored gestation and immunisation scheduling charts to monitor their cows' health, growth, and productivity. Notably, this service costs farmers only three Kenyan shillings (KES) per text (US$0.03). Furthermore, the usage of this application is enthusiastically growing as the subscription base is clearly indicating that the farmers are finding this application valuable. As a result, Kenya's dairy production is becoming more efficient, realising market liberalisation and considerably bolstering domestic milk production for domestic and export dairy demands.[29]

In conclusion, APET is encouraging African governments to actively offer agricultural extension services to their farmers using various technologies. But this can be accomplished by pursuing active investments, public-private partnerships, and the rollout of extension services using affordable technology. APET believes that this can make the provision of extension services easily accessible and subsequently increase private sector participation and interest. On the other hand, APET is also encouraging African farmers and entrepreneurs to harness and exploit the extension services-enabling technologies to improve their decision-making and skills in agricultural production and strengthen post-harvest practices. By so doing, subsistence and small-scale farming can improve in Africa and strengthen nutritional food security in alignment with AU's Agenda 2063 aspirations.

Featured Bloggers – APET Secretariat

Justina Dugbazah

Barbara Glover

Bhekani Mbuli

Chifundo Kungade

[1] https://au.int/en/auc/priorities/food-security.

[2] https://www.nepad.org/caadp/publication/ending-hunger-africa-elimination-of-hunger-and-food-insecurity-african-2025#:~:text=The%20African%20Union%20has%20set,Union%2C%202014%2C%202015).

[3] https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals?utm_source=EN&utm_medium=GSR&utm_content=US_UNDP_PaidSearch_Brand_English&utm_campaign=CENTRAL&c_src=CENTRAL&c_src2=GSR&gclid=CjwKCAjwkYGVBhArEiwA4sZLuOVVAs0h-8EHZAjiy6WBjWVvv_Y3e7XwLyHmtxuN-vYG6EHcnGz82xoCLVYQAvD_BwE#zero-hunger.

[4] Climate change and food security: risks and responses. https://www.fao.org/3/i5188e/I5188E.pdf.

[5] https://www.fao.org/3/w0078e/w0078e05.htm.

[6] Agricultural Productivity Growth, Resilience, and Economic Transformation in Sub-Saharan Africa, IMPLICATIONS FOR USAID. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/BIFAD_Agricultural_Productivity_Growth_Resilience_and_Economic_Transformation_in_SSA_Final_Report_4.20.21_2_2.pdf.

[7] Bjornlund V., Bjornlund H., Van Rooyen, A.F., Why agricultural production in sub-Saharan Africa remains low compared to the rest of the world – a historical perspective, International Journal of Water Resources Development, 2020, 36, 20-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2020.1739512.

[8] Henning Bjornlund, Andre van Rooyen, Jamie Pittock, Vibeke Bjornlund. (2021) Changing the development paradigm in African agricultural water management to resolve water and food challenges. Water International 46:7-8, pages 1187-1204.

[9] Gamuchirai Chakona, Charlie M. Shackleton, Food insecurity in South Africa: To what extent can social grants and consumption of wild foods eradicate hunger?, World Development Perspectives, Volume 13, 2019, Pages 87-94, ISSN 2452-2929, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2019.02.001.

[10] https://www.worldenergy.org/assets/images/imported/2016/10/World-Energy-Resources-Full-report-2016.10.03.pdf.

[11] https://www.fao.org/3/W5830E/w5830e03.htm.

[12] https://www.wfp.org/countries/Tanzania?

[13] https://www2.shu.ac.uk/PDAN/tanzanian_food_security_and_health.html#:~:text=The%20level%20of%20food%20insecurity,have%20poor%20food%20consumption%20levels.

[14]https://agricultureandfoodsecurity.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40066-018-0225-x .

[15] http://sri.ciifad.cornell.edu/countries/tanzania/index.html.

[16] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/32170961_Reforming_Tanzania's_Agricultural_Extension_System_The_Challenges_Ahead/link/5ce3e3ad458515712eb8c5a6/download.

[17] https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Using-Information-and-Communication-Technologies-of-Mtega-Msungu/fe024a413470b600f71d7ebda9b69304f892d04c#citing-papers.

[18] Sanga, Camilius & Tumbo, Siza & Mlozi, Prof & Muhiche, Lupyana & Haug, Ruth. (2014). On the Development of the Mobile-based Agricultural Extension System in Tanzania: A Technological Perspective. International Journal of Computing and ICT Research (IJCIR). 8. 49-67.

[19] Fue, Kadeghe & Geofrey, Anna & Mlozi, Prof & Tumbo, Siza & Haug, Ruth & Sanga, Camilius. (2016). Analyzing Usage of Crowdsourcing Platform ‘Ushaurikilimo’ by Pastoral and Agro-Pastoral Communities in Tanzania. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning. 13. 3-22.

[20] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2013/03/27/morocco-farmers-benefit-opening-markets-agricultural-modernization.

[21] IBM develops cloud-based plan to help Moroccan farmers. https://www.biztechafrica.com/article/ibm-develops-cloud-based-plan-help-moroccan-farmer/4655/.

[22] https://www.ata.gov.et/programs/production-productivity/research-extension-projects/.

[23] https://gro-intelligence.com/insights/agricultural-extension-services-in-africa.

[24] https://afr-corp-media-prod.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/afrexim/African-Trade-Report-2020.pdf.

[25] ADOPTION OF TECHNOLOGIES FOR SUSTAINABLE FARMING SYSTEMS WAGENINGEN WORKSHOP PROCEEDINGS, https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/sustainable-agriculture/2739771.pdf.

[26] Kenya’s dairy sector is failing to meet domestic demand. How it can raise its game. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/agriculture/kenya-s-dairy-sector-is-failing-to-meet-domestic-demand-how-it-can-raise-its-game-81567.

[27] The future of food and agriculture. https://www.fao.org/3/i6583e/i6583e.pdf.

[28] https://disruptingafrica.com/index.php/ICow.

[29] Crowe, M.A., Hostens, M. & Opsomer, G. Reproductive management in dairy cows - the future. Ir Vet J 71, 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13620-017-0112-y.