Obstetric Fistula: Enhancing Preventative Maternal Healthcare For African Women Using Smart Technologies

This is the 07th post in a blog series to be published in 2022 by the Secretariat on behalf of the AU High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies (APET) and the Calestous Juma Executive Dialogues (CJED)

Access to basic and preventative maternal health for African women is regarded as a fundamental human right and essential. Maternal health is not only considered crucial to the health of the mothers giving birth but also the babies being given birth to. Healthy babies will yield to economically healthy citizens, which has direct implications on the socio-economic development of the African continent.

Women represent slightly over 50% of the African population and remain an essential human resource. Thus, their health has significant implications for the continent’s economic development.[1] Recognising the importance of women’s health, African countries should ensure the provision of maternal and preventative health healthcare.

The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal Number 3 strives to ensure healthy lives and promote the well-being of global citizenry of all ages, including pregnant women and the babies they are carrying.[2] Furthermore, the African Union’s (AU) Agenda 2063 envisions a prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable socio-economic development and growth.[3] In addition, the regional African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (Banjul Charter) and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa also recognise women’s right to health as a fundamental right.[4]

Despite calls to improve the health conditions of women across the African continent, African women remain subject to a myriad of healthcare challenges. The World Health Organisation (WHO) reports that African women are highly likely to die from diseases such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), tuberculosis, malaria, maternal and perinatal complications, and nutritional deficiencies, more than other women from other parts of the world.[5]

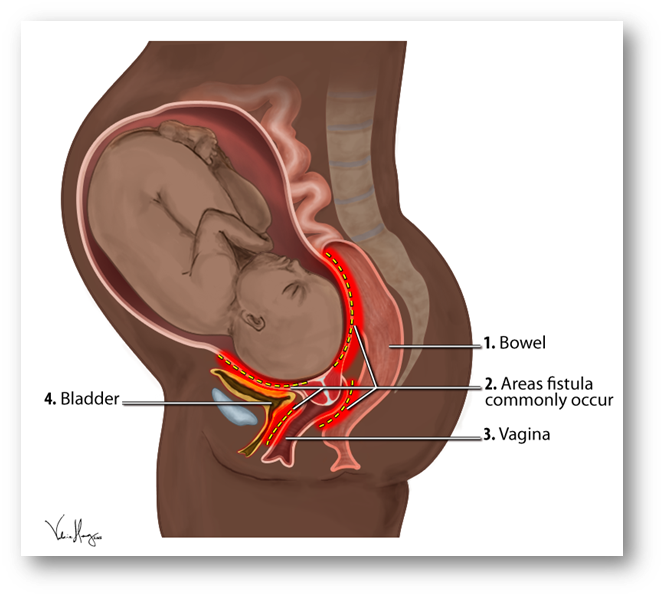

Maternal healthcare remains crucial as it’s a leading cause of death in African Women. One threat to maternal health on the continent is Obstetric Fistula, a “hole formed between the birth canal and bladder and/or rectum, and caused by prolonged, obstructed labour without access to timely, high-quality medical treatment”[6]. This condition can lead to continuous urinary and, in some cases, faecal incontinence[7] and may be triggered by malignancy, radiation therapy, surgery, and traumatic injury.[8]

Figure 1: An illustration of areas where obstetric fistula commonly occurs. SOURCE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Obstetric_fistula#/media/File:Obstetric_Fistula_Locations_Diagram.png

In developing countries such as the African continent, obstetric Fistula can result from prolonged and obstructed labour, often occurring over several days because the unborn baby cannot pass through the pelvis.[9] This may be caused by the big size of the new-born baby since they may not easily pass through the pelvis. In some cases, the foetus may be lying in the wrong position, or the pelvis may be malformed or not fully developed. The prolonged pressure of the baby’s head can damage the blood vessels supplying the tissues of the vagina, bladder, urethra, and rectum. The damage may end up cutting off the supply of oxygen; a condition referred to as ischaemia. Regrettably, this may lead to the death of the affected tissue in the form of necrosis. Subsequently, the dead tissue may then exuviate away, thereby leaving a hole between adjacent organs.[10]

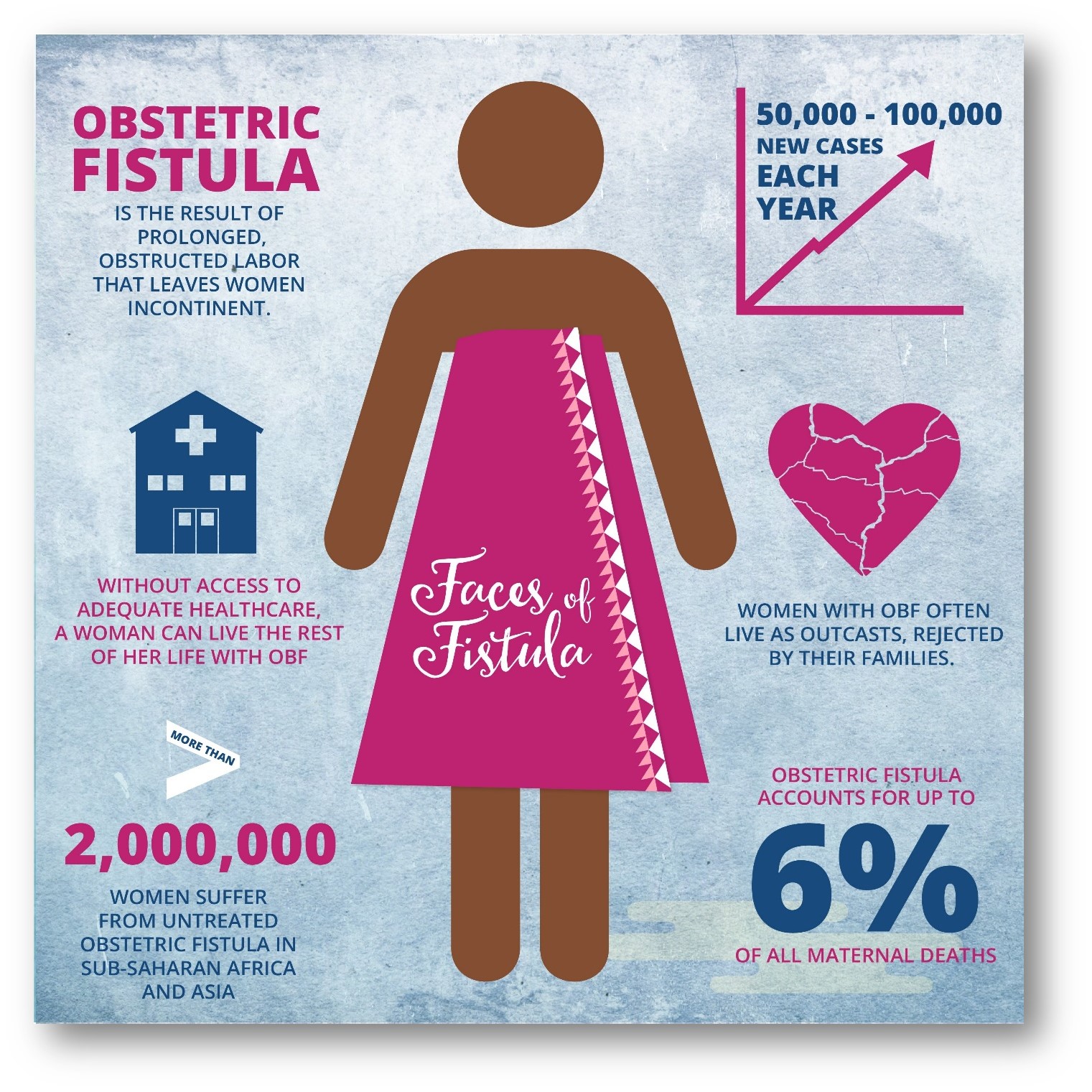

Notably, approximately two (2) million women in Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, across the Middle East region, Latin America, and the Caribbean are living with this obstetric fistula injury. Furthermore, approximately 50 thousand to 100 thousand new cases are reported each year.[11] For instance, in Burkina Faso, the occurrence rate of Obstetric Fistula is reported at 6 out of 10,000 cases amongst gynaecological patients, with more patients affected in rural areas.[12] Leaving this condition untreated can lead to skin infections, kidney malfunction and subsequently cause death among women, especially delivering mothers.

Figure 2: Obstetric Fistula Facts. SOURCE: Mercy Ships UK (https://twitter.com/MercyShipsUK/status/1131454903875002368/photo/1)

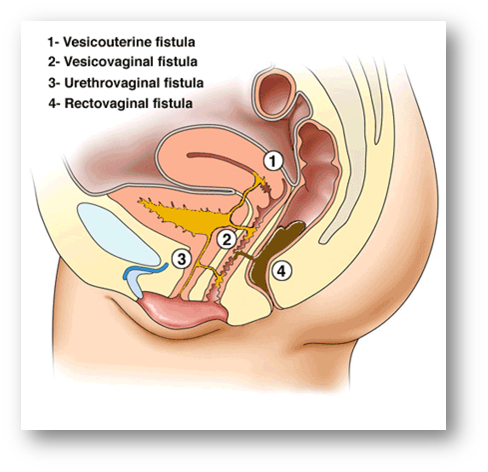

The various types of Obstetric Fistula can include the Vesicovaginal Fistula that occurs between the bladder and vagina and the Urethrovaginal Fistula that occurs between the urethra, known as the bladder outlet and vagina. There is also the Rectovaginal Fistula that occurs between the rectum and vagina; Ureterovaginal Fistula that occurs between the ureters (kidney tubes) and the vagina; and the Vesicouterine Fistula that occurs between the bladder and the uterus (womb). In some cases, more than one type of Fistula may occur simultaneously because of severe damage.[13]

Figure 3: Types of Obstetric Fistula. SOURCE: https://www.healinghandsclinic.co.in/obstetric-fistula-treatment/

The best approach to addressing this challenge is an urgent caesarean section. Thus, Obstetric Fistula has been effectively eliminated in the developed world because of the availability of healthcare facilities such as emergency obstetric facilities and caesarean section services.[14] However, in developing countries, this may not be readily available because of limited resources to detect such challenges during pregnancy or on delivery. There exists limited a limited number of adequately trained and skilled medical staff, as well as the lack of medical supplies and equipment in most African clinics and hospitals.[15] This calls for the formulation of effective solutions

The African Union High Level Panel on Emerging Technologies (APET) notes that the obstetric fistula challenge has been eliminated in developed countries. However, this condition remains highly prevalent within African countries.[16] APET believes that Africa can eliminate Obstetric Fistula by incorporating smart technologies as part of preventative healthcare facilities to monitor this condition among African women. APET further acknowledges that health digital technologies can potentially enhance access to healthcare towards chronic maternal morbidities such as obstetric Fistula.

Uganda and Nigeria are leveraging digital Interactive Voice Response (IVR) technology to identify cases of Obstetric Fistula.[17] The IVR technology enables obstetric fistula screening and can be utilised as a referral hotline. As a hotline, it was developed to cater for inaccessible women, more especially in rural communities, that are living with obstetric fistula conditions. This technology utilises a mobile phone where a caller can dial a toll-free number. Through a consultative conversation, the technology allows the women to answer specific questions that will give insights into their health status. Subsequently, the hotline collects data on the demographics of Obstetric Fistula and experienced barriers against access to treatment.

Once the data has been collected, the women who screen positively within the intervention catchment areas receive follow-up consultation via telephonic consultative conversation from a community healthcare agent. This agent subsequently books the women for a doctor’s appointment and surgery for the patient, where applicable and necessary. Specifically, this technology was created to assist women who cannot read text messages on their mobile phones. This enables access to the most vulnerable women likely to struggle from this condition but lacks information on available preventative healthcare and medical facilities.[18]

The greatest challenge for most women towards accessing basic healthcare is usually money for transport to access basic healthcare. This is observed even in cases where the healthcare facilities and services are subsidised financially by African governments in partnership with developmental partners. Therefore, technologies to enable access to funds for transportation and buying medical supplies, among others, need to be availed to these women. For instance, Mobile money technology has gained traction in trying to address access to funds for transport in places without banking facilities. African countries such as Tanzania are leveraging mobile money through the M-Pesa platform to pay for procedures and medical supplies related to preventative healthcare for such communities without banking facilities. [19]

The United Nations Population Fund has estimated that there are approximately 3000 new obstetric fistula cases in Tanzania.[20] Maternal healthcare in Tanzania is free; however, the transport costs remain a huge challenge for most women.[21] Thus, through the M-Pesa money mobile facility, women from inaccessible villages and without banking facilities can be given transport money through the mobile money platform to travel to nearby clinics and hospitals for treatment. The mobile money project has been spearheaded by the Comprehensive Community-Based Rehabilitation in Tanzania (CCBRT), collaborating with the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) and the telecommunications company Vodacom.[22] They provide patients suffering from obstetric Fistula with transport costs for their repair surgery.

Women who suffer from obstetric Fistula are often subjected to constant incontinence, shame, social segregation, and health problems.[23] Thus, addressing these social segregations and health problems remain crucial when addressing preventative healthcare measures for African countries. Even though approximately 2 million young women live with untreated Obstetric Fistula in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, APET notes that obstetric Fistula can be preventable and treatable.[24] For example, this condition can largely be avoided by delaying the age of first pregnancy, ending the harmful traditional practices that promote obstetric fistula injuries, and timely access to obstetric care. As such, appropriately preventing and managing obstetric fistula conditions using supporting technologies can largely contribute to the Sustainable Development Goal 3 of enhancing maternal health.

In 2010, in Burundi, approximately 40% of women had limited or no access to skilled attendants at birth. The caesarean section rate was estimated to be approximately 4% against the minimum acceptable caesarean rate of 5%.[25] On the other hand, the annual incidence of obstetric Fistula was estimated to range between 0.2% and 0.5% of all deliveries, with 1000 – 2000 new cases per year. Regardless of this comparatively high incidence rate of cases, the national capacity for identifying and managing obstetric Fistula remained limited in Burundi.[26] To address this challenge, the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) set up a permanent referral centre in 2010.[27] This permanent referral centre was established to manage women with obstetric fistula cases. Unlike the one-time surgical fistulae repair ‘camps’ commonly pursued as a joint humanitarian venture, the MSF model of obstetric fistula care went beyond simply the technical act of surgical repair. This centre provided a comprehensive package of obstetric fistula care that promoted both the physical and psycho-social recovery frameworks.

While programmes such as the MSF exist across the continent, there is limited published information, especially within the rural African settings.[28] Therefore, APET is suggesting Africans should not only pursue similar models but also incorporate some of the above-mentioned technologies to strengthen capacity and effectiveness. This can also help enhance their visibility across the African continent and help African countries better address and manage the preventative healthcare operational challenges.

In conclusion, APET suggests that utilising smart technologies to support preventative medicine programmes and monitoring preventable diseases such as obstetric Fistula should be pursued and upscaled across the African continent. APET acknowledges that the reduction and eventual eradication of this condition in Africa can be accomplished just as in the developed countries that have managed to. Eradicating the obstetric fistula condition would also enable rapid socio-economic development.

Featured Bloggers – APET Secretariat

Justina Dugbazah

Barbara Glover

Bhekani Mbuli

Chifundo Kungade

[1] Reaping The Potential Benefits Of The African Continental Free Trade Area For Inclusive Growth: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/aldcafrica2021_en.pdf.

[2] Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3.

[3] https://www.nepad.org/blog/alleviating-maternal-deaths-africa-through-innovation-and-emerging-technologies

[4] https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/report-of-the-commission-on-womens-health-in-the-african-region---full-who_acreport-comp.pdf

[5] GLOBAL HEALTH RISKS, Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_full.pdf.

[6] https://www.unfpa.org/obstetric-fistula#:~:text=Obstetric%20fistula%20is%20one%20of,%2C%20high%2Dquality%20medical%20treatment.

[7] Changole, J., Thorsen, V.C. & Kafulafula, U. “I am a person but I am not a person”: experiences of women living with obstetric fistula in the central region of Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 433 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1604-1.

[8] Priya Narayanan, Marielle Nobbenhuis, Karina M. Reynolds, Anju Sahdev, Rodney H. Reznek, Andrea G. Rockall, Fistulas in Malignant Gynecologic Disease: Etiology, Imaging, and Management, Education Exhibit, RadioGraphics 2009; 29:1073–1083, Published online 10.1148/rg.294085223, https://pubs.rsna.org/doi/pdf/10.1148/rg.294085223

[9] Carmen Dolea, and Carla Abou Zahr, Global burden of obstructed labour in the year 2000, Evidence and Information for Policy (EIP), World Health Organization, Geneva, July 2003: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/bod_obstructedlabour.pdf.

[10] Ali Farzin, Shabir Hassan, Liliana S. Moreira Teixeira, Melvin Gurian, João F. Crispim, Varun Manhas, Aurélie Carlier, Hojae Bae, Liesbet Geris, Iman Noshadi, Su Ryon Shin, Jeroen Leijten, Self‐Oxygenation of Tissues Orchestrates Full‐Thickness Vascularization of Living Implants, Advanced Functional Materials, 10.1002/adfm.202100850, 31, 42, (2021).

[11] Adler AJ, Ronsmans C, Calvert C, Filippi V. Estimating the prevalence of obstetric fistula: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:246. Published 2013 Dec 30. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-246.

[12] Banke-Thomas AO, Kouraogo SF, Siribie A, Taddese HB, Mueller JE (2013) Knowledge of Obstetric Fistula Prevention amongst Young Women in Urban and Rural Burkina Faso: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 8(12): e85921. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085921.

[13] https://www.webmd.com/women/guide/what-is-a-vaginal-fistula.

[14] Semere L, Nour NM. Obstetric fistula: living with incontinence and shame. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(4):193-197.

[15] Improving health worker performance: in search of promising practices, A report by Marjolein Dieleman and Jan Willem Harnmeijer, KIT – Royal Tropical Institute, The Netherlands: https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/improving_hw_performance.pdf

[16] https://journals.co.za/doi/10.10520/EJC160071

[17] TRIPATHI, V., ARNOFF, E., BELLOWS, B., SRIPAD, P. Use of interactive voice response technology to address barriers to fistula care in Nigeria and Uganda. mHealth, North America, 6, dec. 2019. Available at: <https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/33443>. Date accessed: 28 Mar. 2022.

[18] https://www.comminit.com/health/content/use-interactive-voice-response-technology-address-barriers-fistula-care-nigeria-and-ugan

[19] https://www.dw.com/en/mobile-cash-transfers-help-tanzanians-fight-fistula/a-17693495

[20] https://www.dw.com/en/mobile-cash-transfers-help-tanzanians-fight-fistula/a-17693495

[21] https://www.dw.com/en/mobile-cash-transfers-help-tanzanians-fight-fistula/a-17693495

[22] Africa, Mobile cash transfers help Tanzanians fight fistula: https://www.dw.com/en/mobile-cash-transfers-help-tanzanians-fight-fistula/a-17693495.

[23] Semere, Luwam & Nour, Nawal. (2008). Obstetric Fistula: Living With Incontinence and Shame. Reviews in obstetrics and gynecology. 1. 193-7.

[24] https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/10-facts-on-obstetric-fistula.

[25] WHO: WHO Global Health Observatory Data Repository: Burundi statistics summary (2002 - present). [http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.country.country-BDI?lang=en].

[26] WHO: World Health Statistic: Indicator Compendium. 2012, [http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/WHS2012_IndicatorCompendium.pdf].

[27] The Médecins Sans Frontières Charter: https://www.msf.org/sites/msf.org/files/msf_activity_report_2012_interactive_final.pdf.

[28] Tayler-Smith, K., Zachariah, R., Manzi, M. et al. Obstetric Fistula in Burundi: a comprehensive approach to managing women with this neglected disease. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13, 164 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-164.